If you like it, please share it

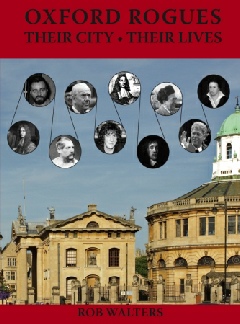

Love them or hate them, rogues mesmerise us. Read about the exploits of the choicest

Oxford rogues - from Bill Clinton, ex-president, to Howard Marks, ex-drug smuggler.

All of them have lived in the city and all have had exciting lives: some were womanisers,

others big drinkers, most were great fun.

Oxford Rogues: Their city, their lives

The rogue male trail commences at Wadham College, a charmingly robust early

17th century building on the eastern side of Parks Road. Little changed since Dorothy

Wadham had the place built following her husband's last wishes, it has discreetly

expanded to the east with new buildings and to the south by acquisition -

During the troubled years of Cromwell's Commonwealth Christopher Wren studied

at Wadham under the wardenship of John Wilkins. Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke and other

scientists of the day visited them for the meetings that ultimately gave birth to

the Royal Society. But these men were scientists, not rogues. The rogue whose life

of debauchery began at Wadham was John Wilmot. He was an Oxfordshire man -

Why start the trail with Wilmot? Well, why not. Wadham is an excellent place to start the trail and the Kings Arms provides a convivial meeting place for rogue hunters.

If you have not heard of Rochester then this little poem might help, it is a much quoted verse that he, rather unwisely, pinned to the door of Charles II's room whilst the monarch was in residence at Christ Church:

Here lies a great and mighty King,

Whose promise none relied on;

He never said a foolish thing,

Nor ever did a wise one.

There were many others poems -

Rochester was educated initially at a school not so far from Oxford, the Burford

Grammar School, where he was described as 'a model pupil.' The school still exists:

it is now a comprehensive and one of the few state schools to have boarding facilities

-

Rochester entered Oxford at the amazingly young age of 12, becoming a 'fellow commoner'

in 1660 -

Thus the young, but brilliant, John Wilmot came up from the countryside to Oxford at a very impressionable age and in a very impressive period of our history. The king was back; the repressive years of the Commonwealth were over; and, as Anthony Wood described it, 'The world of England was perfectly mad. They [the people] were free from the chains of darkness and confusion, which the Presbyterians and the Fanatics had brought upon them.' The pubs were back in full swing; the theatres getting ready to open; and the loyalty of those who had supported the king during the republican years was soon to be repaid.

And how would a young lad of just 12 years fare in the rejoicing city of Oxford?

Badly I'm afraid. It is claimed that the young lord was guided into debauchery by

Robert Whitehall, a fellow of Merton and considerably older than himself. Whitehall

has been described as a minor poet and a great drinker, but not a great thinker.

Some claim that the pair drank at the Saracen's Head, a hostelry long since gone.

According to Derek Honey, Oxford's pub expert, the Saracen's Head stood in the High

Street next to the Angel Inn, also long gone. The Angel belonged to Magdalen College

and was purchased by the university in the 19th century to allow the construction

of the splendid Examination Schools -

Besides the corrupting influence of Whitehall there was at least one other

man who made a great impression on the young lord, his name was James Themut. This

man came to Oxford posing as a medical doctor. His practice was short lived, after

a few months he rapidly made off, taking with him a purse full of ill-

At the very young age of 14 years Rochester was awarded a Master's Degree by Lord Clarendon, his uncle. Clarendon was both Lord Chancellor of England and Chancellor of Oxford University. He was also very influential in Charles II's new government and in awarding the degree may well have been rewarding the son for the loyalty of the father. The first Earl of Rochester, John Wilmot's father, had aided the escape of the Charles II during the civil war and died whilst an adviser to the king in exile. Clarendon was also an adviser to the king during the long wait for the restoration, later earning himself a special place in the memoirs of Oxford. He wrote a great book on the civil war, the royalties of which were donated to the University in order to construct a new building to house the Oxford University Press. That edifice, The Clarendon Building, lies just to the south of Wadham College, at the junction of Parks Road and Broad Street.

His academic and moral education complete Rochester needed a little rounding

off. With the King's permission he embarked on a grand four-

At court he regularly disgraced himself in deed and in poetry. His poems are at best risqué, and at worst pornographic. For all of that his verse has been much admired by many (including Graham Greene who wrote a biography of him), and are said to be excellently composed and insightful. The more salacious poems include:

The Imperfect Enjoyment -

Signor Dildoe -

The Debauchee -

Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery -

A Ramble in St. James's Park -

SAMPLE STORIOverES

96 pages

Click below for price and delivery

Paper Book